PFAS and Personal Responsibility: How Much Should We Be Doing at Home?

A reflection on the state of PFAS evidence, exposure, and the responses underway.

In our house we have been making an effort to cut back on plastics. Part of our motivation is to lessen the waste burden and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Another important reason is to reduce our exposure to PFAS, or “forever chemicals.” We’ve made modest efforts like replacing our nonstick pans and investing in a more advanced water filter. However, we’ve also struggled to completely rid our home of plastics. The most painful has been swapping out much of our athletic gear, since waterproof jackets and performance clothing are extremely useful but also among the offenders when it comes to PFAS.

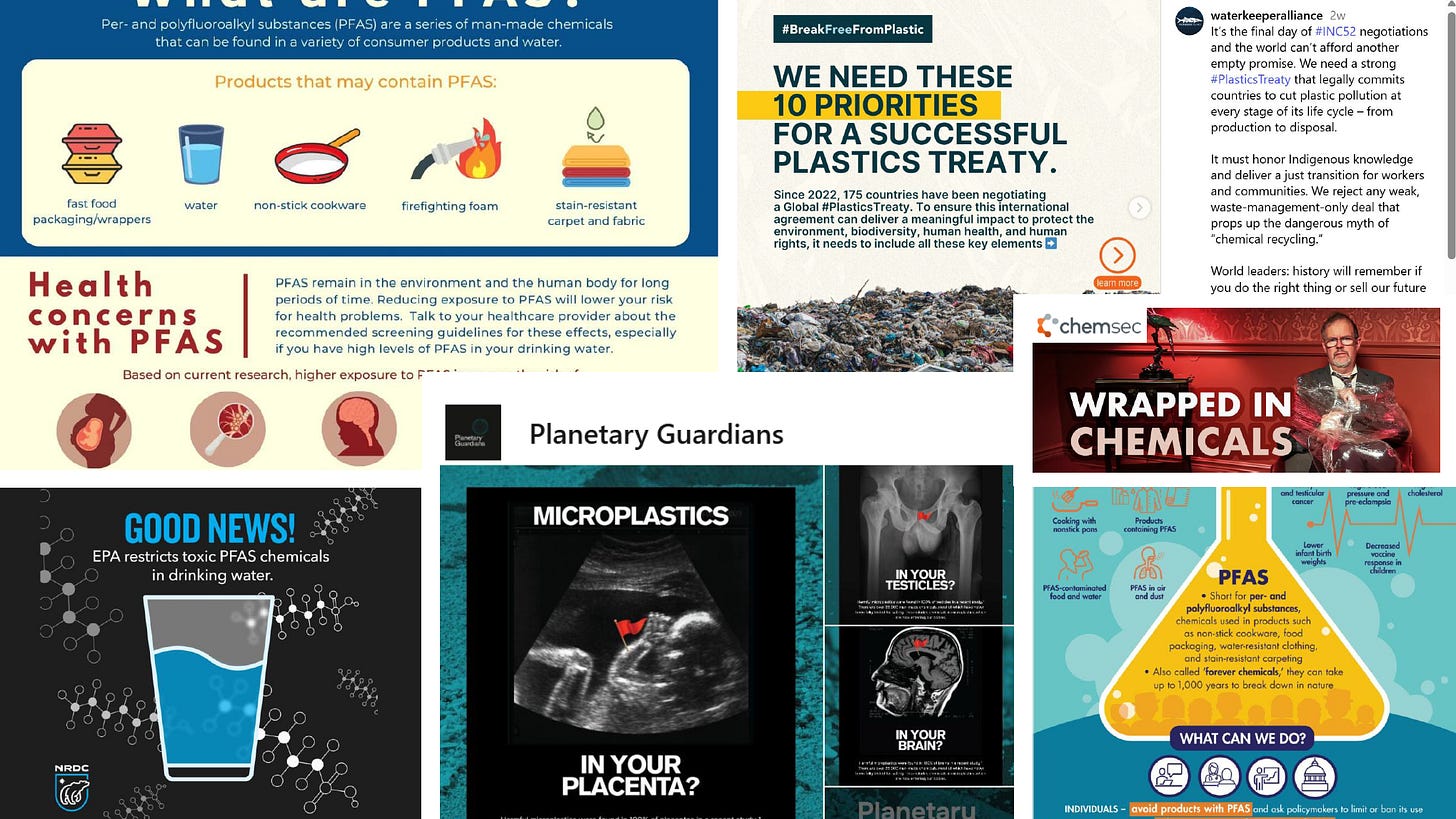

Public awareness of PFAS exposure is rising, fueled by campaigns like Planetary Guardians’ striking visuals (see headline image above) that connect microplastics and human health across social media and public spaces. Yet just as attention grows, efforts to address toxic plastics at the global level are faltering. Just weeks ago, UN negotiations in Geneva collapsed without a binding treaty on plastic pollution, as oil-producing countries and the United States resisted limits on production and toxic additives.

However even with some of the recent media attention, I have friends and families asking how serious the PFAS situation is. My usual response is to share an accessible podcast or article, and there are plenty making the rounds. But I find many of these skim the surface, especially when it comes to the connection between PFAS and health outcomes. They rarely explain where the evidence is strong, where it is limited, and what that means for drawing clear conclusions.

With a background in environmental engineering, I know how slowly both science and regulation move. I also know that early warning signs are often minimized until the harm is undeniable. That tension between uncertainty and precaution sits at the center of the PFAS debate. I wanted to take a closer look at the current state of the evidence and ask whether we should be working harder to eliminate all of these plastic materials from our home?

Quick PFAS 101

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a broad class of synthetic, fluorinated compounds first developed in the 1940s and 1950s to harness durable properties such as resistance to water, oil, heat, and stains. This group includes thousands of individual chemicals, from the older PFOA and PFOS to newer replacements. Their persistence, which has earned them the label “forever chemicals,” comes from the strength of the carbon-fluorine bond. PFAS have been used widely in cookware, food packaging, waterproof fabrics, carpets, cosmetics, electronics, and firefighting foams, becoming deeply embedded in consumer products, industrial processes, and military applications since the mid-twentieth century (EPA, Waste360).

Exposure

This widespread use, combined with the mobility of PFAS, has led to contamination across air, soil, groundwater, surface water, fish, wildlife, and humans (EPA). The most concentrated PFAS releases come from industrial facilities that manufacture or use PFAS, and from locations where aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF) have been heavily used. Decades of AFFF use at military bases, airports, and firefighter training facilities have contaminated groundwater, creating some of the most severe exposure scenarios in the country (EPA, ATSDR).

Drinking water systems are also a pathway of contamination and exposure. A national USGS study of 716 sites sampling both private wells and public water systems between 2016 and 2021 found detectable PFAS in about 45% of all drinking water samples (Environment International 2023). Another USGS predictive model suggests that between 71 and 95M Americans, over 20% of the Lower 48 population, may rely on groundwater containing PFAS for their drinking water (USGS). Moreover, a recent report from the Waterkeeper Alliance revealed PFAS contamination in 98% of tested U.S. waters, especially downstream from wastewater treatment plants (Waterkeeper Alliance).

The result of this widespread contamination is a near-universal human body burden. National biomonitoring data show PFAS in the blood of more than 98% of U.S. residents, underscoring how unavoidable exposure has become (NHANES). The reach extends even to remote ecosystems. Researchers have documented PFAS in Arctic snow and precipitation, carried long distances through the atmosphere and deposited far from any direct source (Science of the Total Environment).

These patterns are compelling and intuitive. It is easy to draw a line from PFAS in the environment to PFAS in our bodies. Yet detection alone does not prove harm. To understand the true health risks, we need to examine the evidence linking exposure to specific outcomes.

Linking PFAS to Human Health Outcomes

Evidence relating PFAS to human health effects has been accumulating for decades, but it was not until the last few years that systematic reviews began to provide some structure and clarity. I’ll focus here on the 2022 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) review which is one of the most comprehensive to date, evaluating a broad range of published studies and assessing how confidently PFAS exposure is linked to specific health effects. As an outcome of the review the committee categorized health outcomes into two categories, sufficient evidence and limited or suggestive evidence.

Sufficient evidence

The committee found sufficient evidence of an association for four outcomes, which I’ll spend a bit more time on here. These are the health outcomes, at this time, you may want to be more concerned about. This is the highest level of confidence and indicates that a positive association has been observed in multiple, well-designed studies in which chance, bias, and confounding can be ruled out with reasonable confidence. The four outcomes are:

Decreased antibody response (adults and children)

Studies show that higher PFAS levels in the blood are linked to weaker antibody responses after vaccination. A 2023 meta-analysis found consistent evidence that exposure to legacy PFAS such as PFOA and PFOS is associated with lower antibody levels following vaccines including tetanus, diphtheria, and measles (Environment International). The National Academies review cited studies that observed reduced immunoglobulin G (IgG), which is the most common antibody in the body and an important marker of long-term immune protection, as well as weaker responses to measles and hand-foot-mouth vaccines in children. The review noted that there is not enough evidence to show PFAS increases the overall risk of common infections. In contrast, a study of adolescents and adults vaccinated against COVID-19 found no association between PFAS exposure and antibody levels (Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Medicine), suggesting that the impact may depend on the type of vaccine, timing of exposure, or the population studied.Dyslipidemia (elevated cholesterol and other lipids)

Research consistently links PFAS exposure, particularly PFOA and PFOS, to elevated cholesterol levels, especially total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (“bad” cholesterol), in both adults and children. Occupational cohorts, community-based studies, and the C8 Science Panel have all reported that higher PFAS levels are associated with increased cholesterol, although the effect may level off at very high exposures (Environmental Health Perspectives). The National Academies review concluded the sufficient evidence categorization for this association, based on multiple well-designed studies across different populations, and identified dyslipidemia as one of the strongest and most consistent health outcomes of PFAS exposureReduced infant and fetal growth

Prenatal exposure to PFAS, particularly PFOA and PFOS, has been consistently linked to small reductions in birthweight and other measures of fetal growth. The National Academies review pointed to studies that show a consistent downward effect on birthweight, around 70 to 80 grams lower per log increase in maternal PFAS levels. Large, multi-cohort studies such as the NIH ECHO program also report that higher prenatal PFAS levels are associated with lower birthweight for gestational age, reinforcing the consistency of the findings across different populations. Mechanistic studies, which investigate the biological processes that explain how exposure leads to health effects, suggest that PFAS may disrupt hormones or interfere with placental transport of nutrients and oxygen, which could explain the observed impacts on growth (Environmental Health Perspectives). More recent mixture and cohort analyses continue to show small but generally negative associations between PFAS exposure and birth outcomes, even when individual results are modest or not statistically significant (Environment International, Toxics).Increased risk of kidney cancer

The link between PFAS exposure and kidney cancer is among the strongest observed. A large study within the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, which followed more than 150,000 U.S. adults and collected blood samples years before diagnosis, found that higher serum PFOA levels were associated with an increased risk of renal cell carcinoma, with clear evidence of an exposure–response trend (La Medicina del Lavoro). Community-based research from the C8 Science Panel also reported higher kidney cancer risk in populations exposed to PFOA-contaminated drinking water (Journal of the National Cancer Institute). A 2023 meta-analysis confirmed elevated kidney cancer risk with PFAS exposure, while noting some limitations and potential confounding. The National Cancer Institute highlights these findings, emphasizing consistent risk increases at higher levels of exposure (National Cancer Institute).

Limited or suggestive evidence

In addition to the above sufficient evidence, the committee also found limited or suggestive evidence of an association for several other outcomes. This category indicates that the evidence suggests an association, but the findings may be limited by a smaller number of studies, inconsistencies between studies, or methodological limitations. These outcomes include breast cancer, altered liver enzymes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, testicular cancer, thyroid disease and disfunction, and ulcerative colitis.

These findings reveal a pattern of impact across immune function, metabolism, development, cancer risk, reproductive health, endocrine function, and inflammatory disease. While the evidence is not yet definitive for every health outcome, it is conclusive for several. For other outcomes such as breast cancer, thyroid dysfunction, and ulcerative colitis, the body of research continues to grow, and the signals point toward genuine concern. Taken together, the evidence makes a strong link between PFAS exposure and real health risks overall.

Dose Response

It is important to recognize that PFAS health effects follow a dose-dependent relationship. While almost everyone in the United States has detectable PFAS in their blood, with average levels of about 4.25 ng/mL for PFOS and 1.42 ng/mL for PFOA (ATSDR), these averages mask large differences across communities. Residents living near industrial sites or military bases where firefighting foam was used often have blood levels dozens or even hundreds of times higher than the national average, with some communities reporting serum concentrations above 100 ng/mL (ATSDR).

To help interpret individual results, the National Academies recommend three ranges of serum PFAS: less than 2 ng/mL where adverse health effects are not expected, 2 to 20 ng/mL where health effects are possible, and greater than 20 ng/mL where risks are increased (NASEM).

Taken together, the evidence shows that PFAS exposure is clearly linked to several health outcomes, but the dose may matter. For most people with low to moderate exposures, risks may be smaller and harder to detect, while highly exposed populations face much greater concern.

The Fight Against PFAS

So with the above evidence, what can realistically be done about PFAS, and how much responsibility should fall on individuals? Personal choices can help reduce exposure, but they cannot solve a problem of this scale. The real responsibility lies with systemic solutions: stronger government regulation to prevent new contamination, corporate accountability for cleaning up existing pollution, and international agreements to curb production and use.

In 2024, the Environmental Protection Agency set the first legally enforceable drinking water standards for PFAS in the United States, establishing Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) of 4 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOA and PFOS, along with a non-enforceable health goal of zero (EPA). This was a historic milestone, estimated to protect more than 100M people. Federal funding is beginning to support upgrades to water treatment systems, with technologies being deployed to remove PFAS for tap water. These methods can remove PFAS before water reaches taps, but they are costly and technically complex. In Pennsylvania, Representative Chrissy Houlahan announced $500,000 in federal funding to help Chester County upgrade its water infrastructure, framing it as part of a broader effort to safeguard drinking water and protect public health (Houlahan). In other places, implementation has already faced delays and resistance, with critics pointing to the costs of compliance for utilities and industries (Guardian).

Some states, however, are beginning to hold corporations accountable. New Jersey reached a landmark PFAS settlement last month, securing funds to clean up drinking water systems and hold chemical manufacturers accountable (NY Times). These lawsuits represent more than just financial compensation. They send a signal that companies profiting from PFAS will face responsibility for long-term contamination. Similar litigation is playing out across the country, forcing producers to acknowledge their role.

Globally, progress has been more uneven. At the 2025 plastic pollution negotiations in Geneva, countries again failed to reach a binding treaty to limit plastics and toxic additives. Oil-producing states and the United States resisted measures to cap production, leaving PFAS regulation entangled with broader battles over fossil fuels, trade, and manufacturing (Guardian).

Taken together, these developments reveal a mixed picture. Regulation is advancing but vulnerable to political pushback. Lawsuits are securing accountability, but only where courts and states are willing to act. International negotiations have stalled. Infrastructure upgrades are starting, though unevenly across communities

Reducing Personal Exposure

So the question remains how much effort and time should you really put into reducing your own exposure? I’ll again argue that most of this burden should be put on corporations and the government so you may want to use your valuable time pushing for stronger regulations by contacting your representatives and supporting broader action.

That said, there are still meaningful steps you can take, especially if you have higher exposures. The greatest risks are for people who work in facilities where PFAS are used, or who live near industrial plants, airports, or military bases where firefighting foams have been applied. In these situations, reducing exposure is especially important. For everyone else, if you are looking to lower your personal risk, here are a few practical places to start at home:

Water

Certified household filters, such as activated carbon and reverse osmosis systems, can significantly reduce PFAS in drinking water (EPA). These systems require upkeep and investment, but they are one of the most reliable ways to limit exposure at home.Food containers and cookware

PFAS are common in grease-resistant food packaging like fast-food wrappers and microwave popcorn bags, and they can migrate into food. Nonstick pans made with Teflon can also degrade and release PFAS at high heat. Safer alternatives include stainless steel, cast iron, or PFAS-free ceramic cookware (Foods, Ecology Center).Clothing, textiles, and dust

Waterproof jackets, stain-resistant carpets, and performance gear are often treated with PFAS. These materials also shed particles that accumulate in household dust, which can be ingested or inhaled, especially by children (National Academies). Choosing PFAS-free textiles and vacuuming with a HEPA filter can help reduce exposure.

Future Considerations

Looking back at the evidence and the actions underway, it is clear that PFAS is both a personal and systemic challenge. The science shows real health risks, and while individual steps at home are important, lasting progress will depend on broader action. To close, here are three areas that deserve some attention moving forward.

Public health

Priorities now include fully implementing the new drinking water standards, offering clear clinical guidance to exposed populations, and accelerating the development of safer, non-fluorinated alternatives that can end the cycle of contamination.Research

PFAS are not a single chemical but a family of thousands, and toxicological data exist for only a small fraction of them. As legacy compounds like PFOA and PFOS are phased out, they are being replaced by newer PFAS that remain largely unstudied, creating an urgent need for expanded research.Prevention and alternatives

Broader systemic change will require rethinking our reliance on PFAS in consumer products and plastics. Global plastics production is forecast to rise sharply if current trends continue. The United Nations Environment Programme reports that plastic production and plastic waste are expected to triple by 2060 under a business-as-usual scenario, driven by rising demand and lack of systemic change (UNEP).